Bob Aumann Bargains in Cancún

Knot Theory to Game Theory - with that little Scandinavian Prize along the way

Two decades ago, Robert Aumann got the Nobel Prize in Economics.

I have met Bob a few times as he is called in the US. In Israel, he is known as Yisrael and in Europe - he is often called Johnny.

He is a good friend of my professor in Minnesota Leo Hurwicz because they were both good friends of Ken Arrow of Stanford. Bob and Leo spent many summers in Palo Alto in the 1950s and 60s - the then home of mathematical economics workshops.

Bob is deeply religious. He is a strong supporter of the State of Israel. That is why he went to Hebrew University to teach although he had standing offers from Stanford, Harvard and Princeton.

Robert J. Aumann is the granddaddy of game theory. He once wrote a paper in the Annals of Statistics called "Agreeing to disagree." [Many disagree with his political views.]

He wrote a paper in the Journal of Economic Theory entitled "Game theoretic analysis of a bankruptcy problem from the Talmud" (more on that later).

He started his life as a pure mathematical theorist. Pure math, in the 1950s was still the high priesthood. He wanted to be the highest of high priests - hence he did his PhD on knot theory. Later, he said, "Knot theory was great because it was so useless."

He believed in Hardy's idea of pure mathematics: Any hint of application ruins the charm. Ironically, knot theory found a great set of applications in studying the structure of the DNA.

A Digression into Quantum Computing: Meet Google Willow

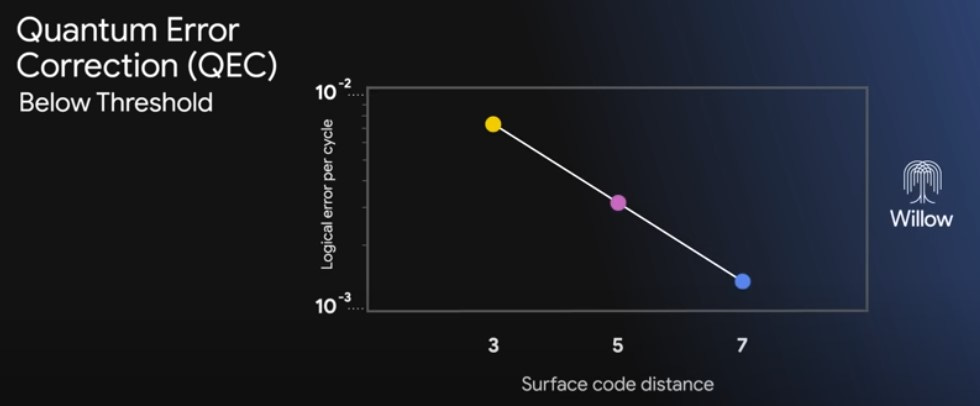

It might prove very useful in quantum computing - some people hope. Recall the quantum computer chip “Willow” Google unveiled. It is the first qubit chip that does “error correction” faster as it scales up to 105 qubits. Potential applications: DNA structure constructions, targeted drugs, batteries, fusion technologies.

https://blog.google/technology/research/google-willow-quantum-chip/

Armed with Peter Shor’s Algorithm (that won the Gödel Prize), will it make bitcoins useless? To do that, it would need a chip with 1,500,000 qubits. Not happening anytime soon.

Another digression: Godfrey Harold Hardy on Applied Mathematics

GH Hardy, once did some work in mathematical genetics. One of his formulas became famous in mathematical genetics: "The Hardy (Weinberg) Formula". Late in life, Hardy was asked whether he had any regrets in life. He answered: "Indeed, I regret proving this theorem in mathematical genetics. It is useful, so I'm sorry to have done it."

Like Leo, Bob is a great storyteller

After completing the doctorate on knots, he did a postdoc at Princeton. One day he was hitchhiking from New Jersey to New York. A car stops, the driver says: "Young man, where are you going?" So he says "I'm going to the city." And he replies: "Southern Germany via Brooklyn!"

Bob Ties the Knots

It was in the fall of 1954 that I got the crucial idea that was the key to proving my result. The thesis was published in the Annals of Mathematics in 1956; but the proof was essentially in place in the fall of 1954.

That’s Act I of the story. And now, the curtain rises on Act II – fifty years later, almost to the day.

It’s 10 p.m., and the phone rings in my home. My grandson Yakov Rosen is on the line. Yakov is in his second year of medical school. “Grandpa,” he says, “can I pick your brain? We are studying knots. I don’t understand the material, and think that our lecturer doesn’t understand it either. For example, could you explain to me what, exactly, are ‘linking numbers’?” “Why are you studying knots?” I ask. “What do knots have to do with medicine?” “Well,” says Yakov, “sometimes the DNA in a cell gets knotted up. Depending on the characteristics of the knot, this may lead to cancer. So, we have to understand knots.”

I was completely bowled over. Fifty years later, the “absolutely useless” – the “purest of the pure” – is taught in the second year of medical school, and my grandson is studying it. I invited Yakov to come over, and told him about knots, and linking numbers, and my thesis.

[Here is the published version of Bob’s PhD thesis. As he says, except for the “Application” part, this is pretty much what his thesis was. It was *a partial* solution of an open problem that nobody knew how to solve. That included his thesis supervisor.

http://www.math.huji.ac.il/~raumann/pdf/Asphericity%20of%20Alternating%20Knots.pdf]

Bob Story from Cancún

Now, I would like to narrate one of *my* stories about him.

A few years ago, the Latin American Econometric Society had its conference in Cancún, Mexico. I went to present a couple of papers there.

Bob Aumann was the keynote speaker.

One of our tours was to go to Chichen Itza - the Mayan ruins - on a bus.

Bob had a problem with his left knee. So, he sat in the front row of the bus. I have noticed that in conferences people have great reluctance to sit next to big names. Bob certainly was a big name.

I had met Bob before, so I had no hesitation sitting next to him. We were chitchatting. He asked me how old I was. When I mentioned 1957, he muttered, "My son *would have been* exactly the same age as you."

If you are puzzled by why he said his son "would have been" the same age, you need to realize that his son was no longer alive. In fact, in his paper on Talmud, a small dedicatory sentence appears.

"Dedicated to the memory of Shlomo Aumann, Talmudic scholar and man of the world, killed in action near Khush-e-dneiba, Lebanon, on the eve of the nineteenth of Sivan, 5742 (June 9, 1982)."

One of the basic contributions that Bob made for which he won the Nobel is bargaining theory.

The bus stopped at one market selling traditional Mexican stuff.

Mexican markets often sell unpredictable objects. In that particular one, along with the traditional stuff, there was a stall with Nazi German memorabilia. I have no idea why.

Seeing that, Bob was visibly shaken. He was a boy in Frankfurt during the 1930s. "In the store windows in Frankfurt, there was a sign with a light brown background and black lettering,” he remembered. "It was in German. But the letters were written to imitate Hebrew lettering and it said *Juden sind hier unerwünscht* - *Jews are unwanted in this store*."

We go past the unpleasant stall.

Bob collects chess boards from various parts of the world.

He did not have a Mexican one. He had several from India. One he has is at least two hundred years old with pieces made from ivory and the board made out of Burma Teak.

He wanted to buy a marble chess board from Mexico.

He had no idea how much it would cost.

He asked me if I could bargain on his behalf.

I thought this was ironic: The father of bargaining is asking ME to bargain on his behalf.

First rule of bargaining, I told him, was that you should be able to walk away from the deal. If you cannot, you cannot bargain.

I told him we need a discreet signal to settle the price. Bob was carrying a walking stick. I told him to strike the stick twice when he felt happy with the price.

So, we started off around US$100. I pretended to be outraged at the price. The seller softened up. He started coming down - 80...70...60. When he came to $50 Bob banged the walking stick twice.

Executive thought: We did well.

Executive postscript: I had a muse about elections in Yucatán, Mexico. [No, it is not in Spanish - except for a few snippets like the title.]