Double Indemnity (1944): An Actuarial Review

Celebrating eighty years of the movie: Double Indemnity

Main protagonists: Fred MacMurray playing Walter Neff - the insurance salesman; Barbara Stanwyck playing Phyllis Dietrichson - the housewife; Edward G Robinson playing Barton Keyes - the claims underwriter

Directed by – Billy Wilder

Executive confession: I am a great admirer of Wilder*.

[Notice the stark lighting? The shadows are equally sharp as the protagonists. *That* is the classic look of a film noir.]

The movie was based on a book by James M Cain. The book starts with this line:

“A woman was standing there. I had never seen her before. She was maybe 31 or 32, with a sweet face, light blue eyes, and dusty blonde hair. She was small, and had on a suit of blue house pajamas. She had a washed-out look.”

This is how Cain first introduces his dazzling femme fatale, Phyllis Dietrichson, in his hardboiled noir Double Indemnity. [The names of the protagonists in the book are different from the ones used in the movie.]

The movie version of that scene is somewhat different.

Cain was meticulous about the actuarial calculations. The life insurance policy had a face value of $50,000 - and double that for accidental death. (In the movie Walter Neff mentions a specific date in 1938 - see the clip below).

This is how Walter explains to Phyllis the "Double Indemnity" clause of an accident policy: "Look, baby. There's a clause in every accident policy, a little something called double indemnity. The insurance companies put it in as a sort of come-on for the customers. It means they pay double on certain accidents. The kind that almost never happens. Like for instance if a guy got killed on a train, they'd pay a hundred thousand instead of fifty."

The reason why Cain got the figures close to reality was because he himself was (an unsuccessful) insurance salesman before he jumped into writing novels while working as a journalist after his failed attempt to be a stage actor. He found his niche in writing first person narratives. This was how Double Indemnity was structured.

[Walter Neff with his mentor Barton Keyes.]

Executive confession: I used to show the entire movie to my students of Insurance 101 class. I was in good company. The top five insurance companies used to show it to their trainee insurance salesmen. They were always men in the US unlike in Japan where life insurance was sold by the post office and in the Tupperware parties of housewives back then.

A Digression about Real Life to Reel Life

Cain was inspired by the real-life 1927 case of New York housewife Ruth Snyder conspiring with the corset salesman Henry Judd Gray to kill her husband for life insurance money. She was executed for her crime.

https://oldspirituals.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/tom-howard-ny-daily-news-archive.jpg

The insurance money was paid but it was claimed back by the insurance company (there were three policies worth nearly a million and a half in today's money).

Ruth had a ten year old daughter at the time - Lorraine. She testified about how her parents fought all the time. And that her mother would not come back home at night - many nights. After her father was killed by her mother and her lover and her mother went to the electric chair, she became destitute. Her grandmother raised her (other relatives clamored to raise her believing that she was worth a fortune). Lorraine Ellen died in 2016. She had three children. Her life was dogged by her mother’s crime.

Executive thought: It must be hell to be born to notorious parents. I used to know one - Michael Meeropol, an economist - the son of executed Soviet spies - Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Michael’s daughter made a documentary about her grandparents.

Double Indemnity

The Double Indemnity provision for railway accidents and the exclusion for deaths from homicide were both typical of accident insurance policies from the first half of the twentieth century (according to Joseph Mclean’s Introduction to Life Insurance, Edition of 1956).

That policy in the movie had a face value of $50,000 - and double that for accidental death. That fifty thousand would be worth around a million dollars today.

Walter Neff gives a perfect description of why accident insurance is the optimal choice for a homicidally inclined spouse: "When there’s dirty work going on, accident is the first thing they think of. Dollar for dollar paid down, there’s a bigger face coverage on accidents than any other kind. And it’s the one kind of insurance that can be taken out without the insured knowing a thing about it. No physical examination for the accident. On that, all they want is the money, and there’s many a man walking around today that’s worth more to his loved ones dead than alive, only he don’t know it yet."

Walter Neff admits that he had considered bilking the insurance company that employed him long before he met Phyllis. Walter begins by explaining how he has become an expert in heading off policyholders who try to defraud the company. He continues, “You’re like the guy behind the roulette wheel, watching the customers to make sure they don’t crook the house. And then one night you get to thinking how you could crook the house yourself and do it smart, because you’ve got the wheel right smack under your hands. You know every notch in it by heart. And you figure all you need is a plant out front, a shill to put down the bet. Suddenly the doorbell rings, and the whole set-up is right there in the room with you.”

The Making of Double Indemnity

Before even the movie began work, there was a huge problem: The Production Code (of censorship), also known as the Hays Code.

The Hays Code, which began to be enforced in 1934, provided guidelines for "acceptable content" in movies and required all films to receive a certificate of approval before being released. Cain's original story failed on several counts:

(1) Explicit treatment of adultery,

(2) Detailed presentation of criminal methods

(3) Sympathetic treatment of criminal protagonists.

In 1943, an up-and-coming Polish/Austrian immigrant director called Billy Wilder persuaded Paramount Pictures to make an attempt at developing an acceptable treatment of the subject while remaining faithful to Cain’s original story.

The studio hired detective-story writer Raymond Chandler to help Wilder develop the screenplay. By all accounts, Wilder/Chandler/Cain did not get along at all. Chandler’s drinking and Wilder’s in your face attitude did not help. The scriptwriting became a slugfest between the three.

[Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder]

The name of the insurance company was changed from General Fidelity to Pacific All-Risk Insurance Co. The only major concession to the Hays Code was a change to the ending. I will refrain from spoilers if you have not seen the movie.

The opening of the movie was revolutionary. Walter Neff gives away the entire story in the first five minutes.

Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis starts flirting with Walter Neff right off the bat even though the back and forth is all about insurance and nothing else.

Billy Wilder’s choice of Barbara Stanwyck was striking. She was the most glamorous actress at the time. Wilder makes an evil villain out of her. She plays it to the hilt - from the tacky wig to cheap dresses she puts on.

Executive summary of the plot: Walter and Phyllis conspire to kill her husband by buying a life insurance policy in his name without his knowledge. Then they kill him and throw him off a moving train making it look like an accident (hence the double indemnity clause kicks in). It works at first. Then it unravels. Two reasons for unraveling: (1) Neff’s insurance mentor Barton Keyes (played to the hilt by Edward G Robinson) begins to suspect something awry with the huge payout now due to Phyllis. (2) Neff realized that he was being double crossed by Phyllis. She was having an affair with the lover of her step-daughter.

Barton Keyes, the insurance investigator played by Edward G. Robinson, explains to the Pacific All-Risk company’s CEO Mr Norton the killer lines that actuaries love: "Come on, you never read an actuarial table in your life. I've got 10 volumes on suicide alone. Suicide by race, by color, by occupation, by sex, by seasons of the year, by time of day. Suicide, how committed: by poisons, by firearms, by drowning, by leaps. Suicide by poison, subdivided by types of poison, such as corrosive, irritant, systemic, gaseous, narcotic, alkaloid, protein, and so forth. Suicide by leaps, subdivided by leaps from high places, under wheels of trains, under wheels of trucks, under the feet of horses, from steamboats. But Mr. Norton, of all the cases on record there's not one single case of suicide by leap from the rear end of a moving train."

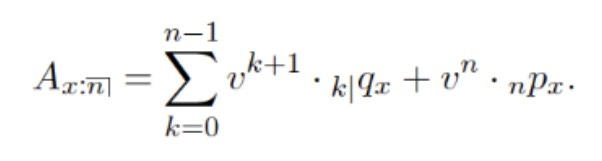

This was how actuarial work used to be: Back office with big fat dusty volumes of qualitative information and another set of books of tables with gobbledigook like this:

[This is a formula for a (contingent) annuity. For each n, (vector) p/q and v, there was a table. Like the medical professional says “arthritis” instead of a “joint inflammation”, actuarial science too, has its own language that confuses the general public.]

The studio allocated a budget for Double Indemnity of $980,000. Wilder stuck to it. The budget allowed him a salary of $44,000 for the four months he spent writing the screenplay with Chandler and $26,000 for the two months he spent directing it. But MacMurray, Stanwyck, and Robinson were paid $100,000 apiece for starring in the movie. The movie made five million at the end (not counting TV reruns and restored digital version sales revenue).

The background score

Miklós Rózsa wrote the score. It flows so naturally that you do not notice it at all. He did not know it then but that kind of doom and gloom score became the defining character of film noir. Billy Wilder never realized that he made the movie in that genre either. Rózsa’s score for the murder scene is a masterpiece. It is a funeral march. The audience does not see the actual deed at all. About the score, he later wrote: “Did I really have to have a G sharp in the second fiddle clashing with a G natural in the violas an octave below? Yes.” His use of Schubert’s Unfinished Eighth was a masterstroke. [It is played in the Hollywood Bowl scene.]

Ignored at the Oscars

The movie had seven nominations. But it did not get any. All went to the movie Going My Way. Wilder felt snubbed by not getting the Best Director Award. He was incensed that he didn't win the Academy Award for the Best Director. When Leo McCarey was running down the aisle to accept the Best Director's Award, Wilder put his foot out and tripped McCarey.

Eighty years on, nobody remembers Going My Way. Double Indemnity routinely comes in the top thirty movies ever made.

*The epitaph of Billy Wilder reads: “I am a writer. But then, nobody’s perfect.”