World War II Toilet Love Story from Brisbane

This place started its life as an air raid shelter. It was designed by Frank Costello (no relation to the Italian American mob boss) along with many other public structures around Brisbane.

Brisbane was the major city in Queensland and the most northerly major population centre in Australia.

Therefore, military planning headquarters were set up in Brisbane, as were a number of important maintenance, communication, and supply facilities.

General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces, Southwest Pacific, was based in the AMP building at the corner of Queen Street and Edward Street in Brisbane, and General Sir Thomas Blamey, Commander in Chief of the Australian Forces, used the recently constructed University of Queensland buildings at St Lucia.

Thus, Brisbane became a strategic target for Japanese bombing, and rapid action had to be taken to protect the military in the event of air raids.

The demand on materials, services and labour was enormous and military projects took precedence in their allocation. Heavy Anti-Aircraft batteries were built at Victoria Park, Hendra, Pinkenba, Fort Lytton, Hemmant and Balmoral, and coastal artillery batteries were established on Bribie and Moreton Islands.

Before the war, Queensland had a small population and no heavy manufacturing industries. To help overcome these problems, some buildings were prefabricated and standard designs for many structures were used. Designs took into account the scarcity of skilled labour and of some materials.

The Brisbane City Council took responsibility for Air Raid Precautions activities, including establishing an Air Raid Warden system, firefighting systems and constructing air raid shelters.

Queensland Premier William Forgan Smith, ordered the Brisbane City Council to construct 200 public surface shelters in the city area. Work had already started on 15 December, and later another 75 shelters were ordered. Eventually, 237 air raid shelters were constructed - not 275 as advertised.

The air shelters had the specification that they should withstand a 500 lbs bomb exploding at 15 feet above the ground.

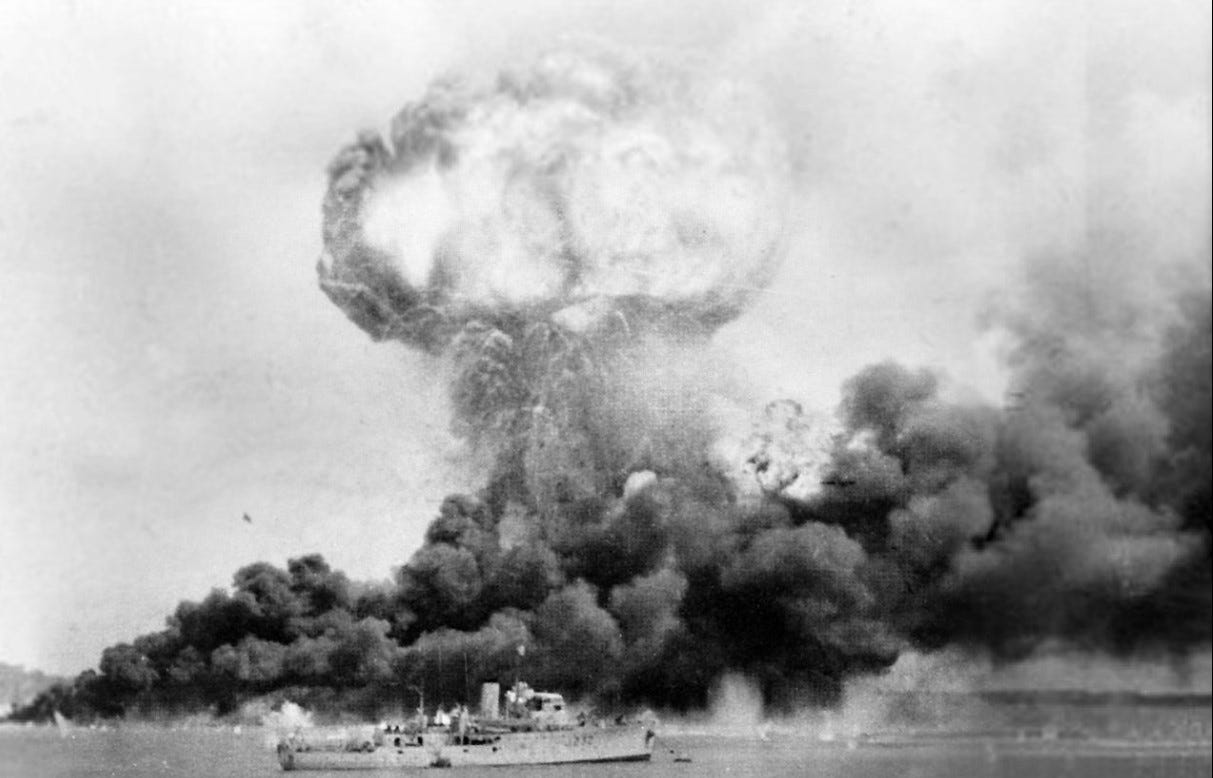

During the first half of 1942, three cities in Australia were bombed: Darwin, Broome and Townsville with three hundred deaths - mostly in Darwin. A final raid took place on the Australian east coast on the night of 30-31 July 1942 when a single bomb was dropped near a house 75 km North West of Cairns.

The attack was led by the same Japanese force that attacked Pearl Harbor.

Americans are often surprised to learn that more civilians were killed, more bombs were dropped and more ships were sunk in Darwin than in Pearl Harbor.

Brisbane saw no bombing. Thus, those 237 shelters were never tested against the real thing.

Of the 237 such concrete prefab structures built, 37 survived the war. Others were demolished by the military.

Only the one in Nundah was converted into a public toilet.

Assuming it can still withstand a 500 lbs bomb blast, it is arguably the safest public toilet in all of Australia. It entered the Queensland Heritage Register on 6 April 2005.

It is a historic building. Fittingly, it sits near the signpost that declares the first white settlement in Queensland - Nundah - then called the German Station. The train station was called the German Station Station!

[I always have a problem with Australian history where aborigines were not counted at all. This is a prime example. The monument was erected more than a century after white folks settled in Queensland and declaring it “First free settlers monument”. Were the locals who lived there for thousands of years did not count?]

Clean India (Swachh Bharat) War - another Love Story

A movie was made about building a toilet in a village in India: “Toilet: A Love Story”.

It was a hit - not just in India but it did roaring business in China.

(trailer of the movie with English subtitles)

The construction of toilets in India is a far bigger public health issue.

Child stunting (low height for age) rates in India, despite rapid economic progress compared with other similar countries, has been much higher. It arises from the widespread practice of open defecation.

You may not associate open defecation with stunting. But, repeated infections through the fecal–oral route resulting in dehydration and malabsorption of nutrients following chronic inflammation of the small intestine has been a persistent and chronic problem among rural poor in India. Therein lies the causal route.

Lack of access to toilets has served as a major driver of open defecation, particularly in rural India. For this reason, expansion of access to sanitation facilities may reduce open defecation which, in turn, may improve infant and child health.

The problem is not new. Over 150 years ago, Scientific American carried an article about this shit.

"The present water closet system, with all its boasted advantages, is the worst that can generally be adopted, briefly because it is a most extravagant method of converting a molehill into a mountain. It merely removes the bulk of our excreta from our houses to choke our rivers with foul deposits and rot at our neighbors’ door. It introduces into our houses a most deadly enemy. Scientific American (July 24, 1869:57)."

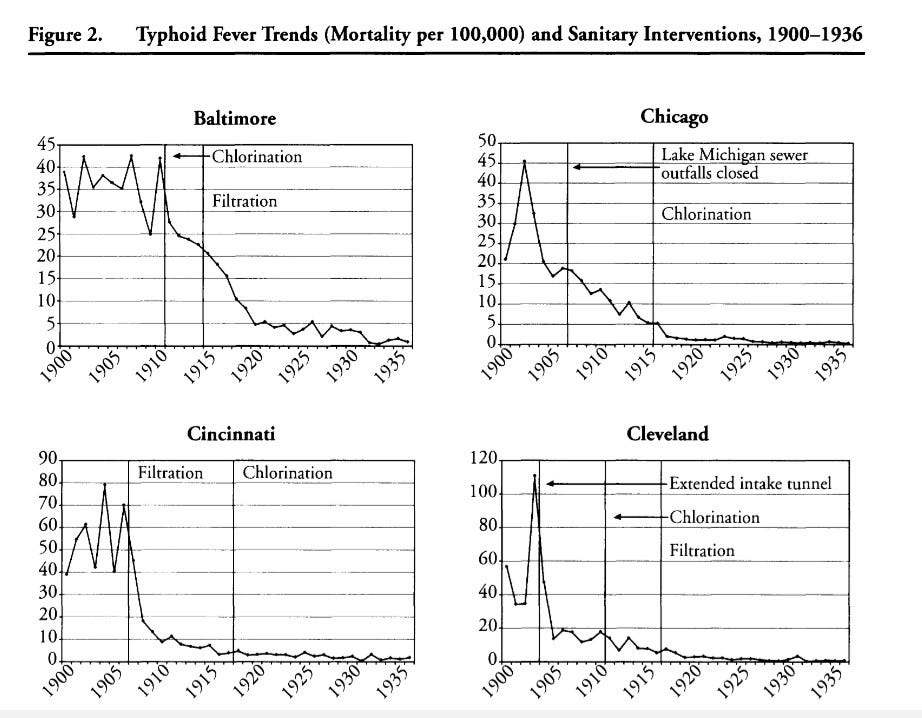

Between 1900 and 1940, introduction of clean water in urban areas saw the US child mortality drop by 80 percent from all causes. In the US, open defecation was not the problem but fecal matter directly polluting the water - was.

A recent paper https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-71268-8

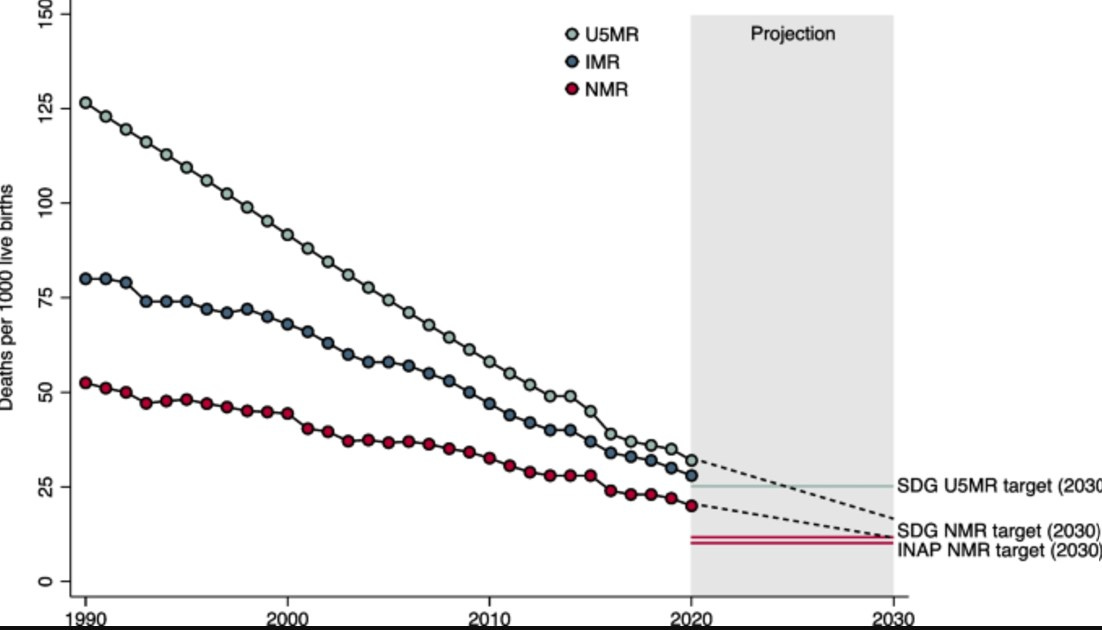

examines the relation between toilet construction in India and child mortality. The researchers exploit the time difference in the construction of toilets in different target areas and examine the child mortality. They found that the total national impact of the toilet project has reduced child mortality between 50,000 and 70,000.

[At the current rate, the mortality for under 5 will be better than what the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) has targeted.]

This effect is a modest 0.5 change in death rate (per 1,000). But these are early days. If we recall how such policies impacted child mortality in the US a century ago, the impact became clear decades later. Thus, the magnitude of the impact of such a policy in India may take a decade to manifest itself.

A Bangladesh Digression

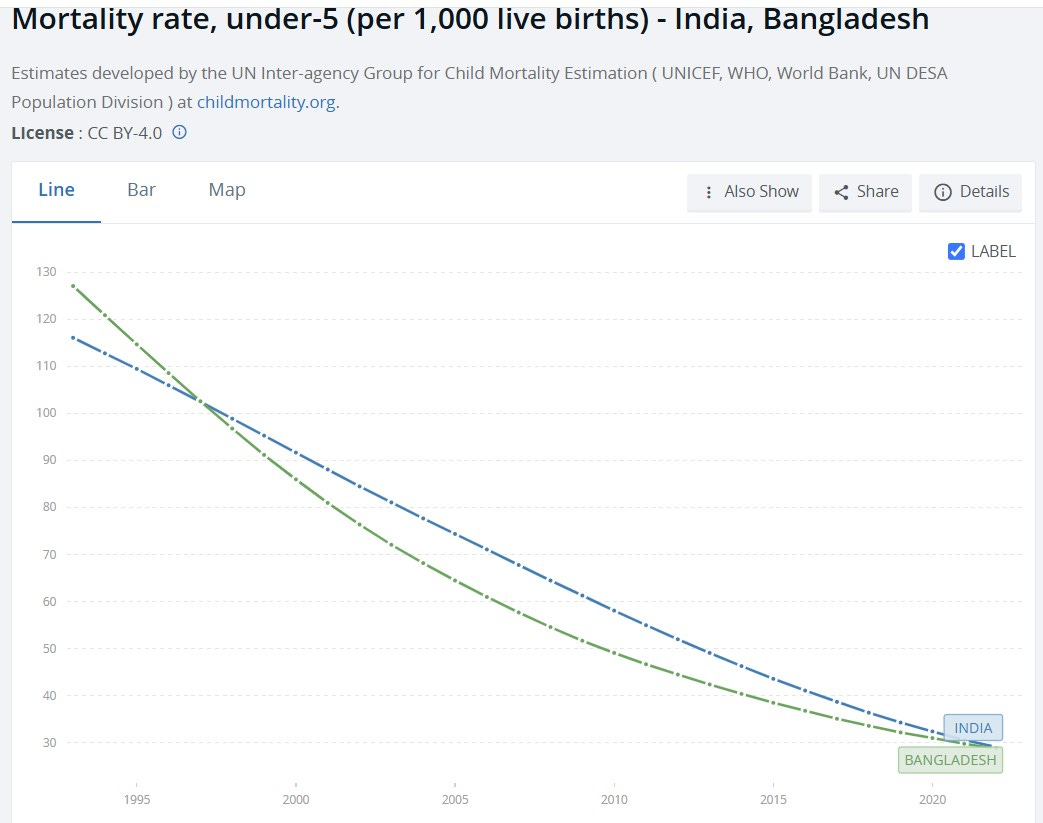

In the past decade, a constant criticism of India’s effort for the reduction of child mortality has been: Why are you lagging behind Bangladesh? We are hearing less of it these days. The picture below explains why.

Executive result: Under-5 mortality rate in India is now lower than that of Bangladesh today. [The rates were higher between 1997 and 2021.]

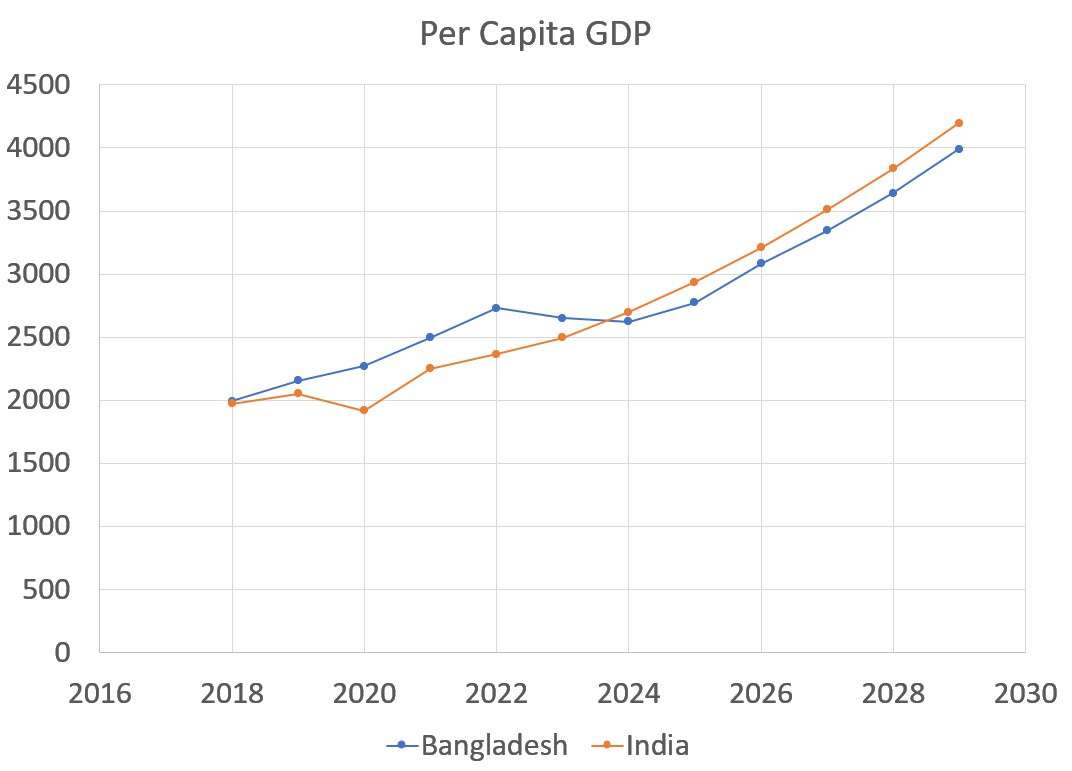

Incidentally, the refrain about how Bangladesh is overtaking India in terms of per capita income is also being heard less these days than before. Once again, the data tells us why. [Note that these are measured in constant dollars but *not* adjusted for purchasing power. The story does not change if we make that adjustment. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPPC@WEO/IND/BGD]

Executive lesson: Data always speaks louder than vacuous political discourse.

There are pictures and graphs. A typical Tapen combo. The connection between proper toilets and child height is so unexpected. Tapen doesn't torture data to extract insights; instead, he lovingly coaxes data to tell a compelling story